Jul 31, 2017

A doctor says new full-face masks are a “recipe for disaster.” He wants to measure the breathing resistance in various types of snorkeling tubes.

By Nathan Eagle

Ocean safety advocates are working on ways to gather more data to determine why so many more visitors die snorkeling in Hawaii than local residents.

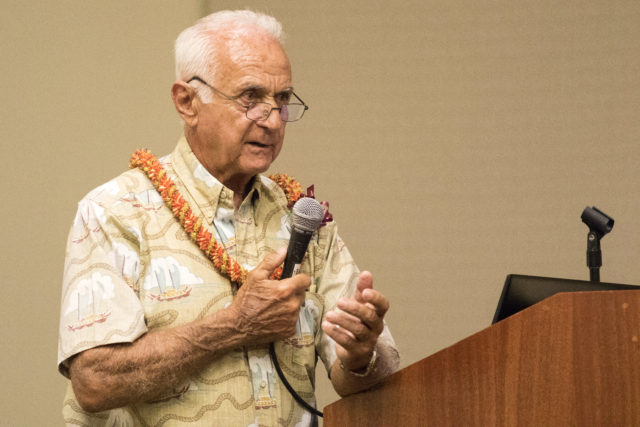

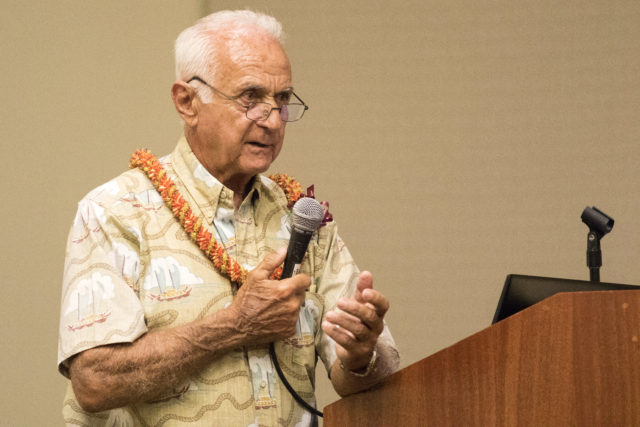

Dr. Philip Foti, an Oahu physician who specializes in pulmonary and internal medicine, is developing a “gadget” that will be able to test different types of snorkel tubes to see which ones create the most resistance while breathing through them.

He told an audience of lifeguards, government officials and others at a drowning-prevention conference Friday in Honolulu that snorkel companies have added new “doodads” to the tubes over the years — mostly aimed at keeping water out — but they may have unintended consequences.

Foti was also concerned about the full-face snorkel masks that are now “all the rage.” He called them a “recipe for disaster,” noting the need to scrutinize this equipment as well.

“I am trying really hard to get a device that will allow us to be the filters of which snorkels to use and which snorkels not to use,” he said. “We need to find out how to test them and then what to do about protecting people from using them.”

Ralph Goto, retired administrator of Honolulu’s Ocean Safety and Lifeguard Services Division, said it’s important for first responders to obtain as much information as they can from each snorkeling-related drowning or near-drowning incident.

“We don’t have the solutions,” he said. “But what we have collectively is the source to gather all that data.”

Hawaii’s visitor-drowning rate is 13 times the national average and was nearly 10 times the rate of Hawaii residents from 2003 to 2012, with snorkeling by far the most common activity in which a fatal accident occurs. Nearly one tourist dies each week while engaged in common vacation activities like swimming, snorkeling, hiking and going on scenic drives.

From 2003 to 2012, state data shows 102 visitors drowned snorkeling, compared to 13 residents.

Carol Wilcox, a lifelong Hawaii resident and former lifeguard, almost became part of those statistics. She shared her 2004 near-drowning experience, which Foti said opened his eyes to additional factors that may contribute to drownings.

Wilcox had just flown back to Oahu after a trip to Canada when she decided to go snorkeling by the Outrigger Canoe Club in Waikiki.

She was making her way to the wind sock roughly 150 yards from shore when she started to have shortness of breath. She soon realized she had no strength in her arms to wave for help, so she began to kick her way back with her long fins.

“My heartbeat sounded like a drum and pretty soon I couldn’t breathe,” Wilcox said. “I realized at that moment why lifeguards can miss the signs of drowning. A wave pushed me up onto the sand and I lost consciousness.”

A lone beachgoer that evening saw Wilcox and she was taken to the hospital.

Foti said he determined she had negative pressure pulmonary edema, which is caused by an upper airway obstruction generating enough pressure to pull fluid from the arteries that take blood to the lungs.

He and Wilcox question what role her snorkel played in the incident, since it was one with an apparatus attached to the top of the tube to keep water out, possibly restricting the flow of air. And they question the role of her recent air travel.

There are still many questions at this point, but Foti said additional data from first-responders and his device to measure snorkel tubes’ breathing resistance will help provide answers that could eventually be used to advise the public on what equipment is safest to use.

Smoking, drinking and certain prescription pills could also make someone more susceptible to this condition, he said.

“We have a lot of work to do,” Foti said.

He added that increasingly popular snorkeling masks that cover the entire face may present similar problems.

For starters, he said there is dead space ventilation in the device that seems greater than in the standard snorkel tube. That dead space can cause carbon dioxide buildup.

California resident Guy Cooper, whose wife drowned last year while snorkeling off the Big Island, has been trying to warn the public about the potential hazards of full-face masks like the one his wife was wearing.

Cooper has said the carbon dioxide buildup in the mask could cause someone to become disoriented or lose consciousness, not to mention other possible hazards such as its difficulty to quickly remove in an emergency.

Cooper’s advocacy prompted county officials on the Big Island, Maui, Kauai and Oahu to start keeping track of the type of snorkeling equipment that was worn in drowning.

“You can’t interview the people who have had fatal drownings but we can interview the people who survive,” Goto said. “It’s important for us as first responders to get as much information as we can.”

Earlier in the day, ocean safety officials held a press conference to share information on public-service announcements that will be shown in hotel rooms for visitors to see.

Honolulu Emergency Services Director Jim Howe provides some of the details in this video below. Additional videos from the press conference can be found on Civil Beat’s YouTube page here.

Mar 16, 2017

A woman’s drowning spurs officials to consider the possible hidden dangers of full-face snorkeling masks.

By Nathan Eagle

Lifeguards in Maui have begun tracking equipment worn by snorkelers who drown in their jurisdiction and other counties appear poised to do the same.

A state water safety committee on Wednesday heard poignant testimony from the husband of a California woman who drowned off the Big Island last year while wearing a new type of snorkel mask that he thinks may have contributed to her death.

On Wednesday, in a boardroom at the Hawaii Convention Center, Guy Cooper took a deep breath and regained his composure before continuing the story of how his wife drowned in September while snorkeling off the Big Island.

The Hawaii Drowning and Aquatic Injury Prevention Advisory Committee, a group of ocean safety experts, state and county officials, tourism industry leaders and others, put Cooper on its agenda after he raised concerns about the role of the full-face snorkeling mask his wife had been wearing. The committee is now co-chaired by Gerald Kosaki, a Hawaii County Fire Department battalion chief who oversees ocean safety, and Ralph Goto, retired administrator of Honolulu’s Ocean Safety and Lifeguard Services Division.

“On one hand you have an activity rife with significant physical demands, then you exacerbate the situation by adding a new piece of inadequately vetted equipment with inherent design flaws,” Cooper said. “A perfect storm.”

The 68-year-old retired nurse from Martinez, California, has also complained about significant gaps in data collection by government agencies.

He’s calling for a database that logs information about the equipment worn in each drowning so authorities can analyze it for dangerous trends, much the same way that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration collects data to determine if a particular type of airbag is faulty in fatal car crashes.

He isn’t sure the Azorro mask his wife, Nancy Peacock, 70, bought on Amazon is the culprit. But he isn’t sure it’s not either.

And that’s why Cooper, and now a growing list of health and ocean safety officials in Hawaii, are looking at collecting the data necessary to better evaluate the product and possibly even conduct controlled scientific studies on it.

Some people who have tried the full-face masks, a next-era design in snorkeling, have complained that they leak and are difficult to remove quickly because of the heavier straps. Some have cited the potential for carbon dioxide to build up and cause fainting.

Cooper said a surfer found his wife floating on her back in Pohoiki Bay with the mask partially pulled up over her nose.

“That tells me she was in trouble and tried to get the damn thing off — too late,” he said.

Colin Yamamoto, Maui County’s Ocean Safety battalion chief, met with Cooper in January.

“What was intriguing to me is we have no data on these,” Yamamoto said. “It’s something we never thought about.”

Yamamoto has directed Maui County lifeguards to start documenting what type of snorkeling equipment was used in drownings.

Fire officials from the other counties are also moving in that direction.

“Maybe we can start individually with each jurisdiction keeping track of that,” Kosaki told the advisory committee. “We can’t make a policy saying, ‘yeah, we’re all going to keep track of it now,’ but I think each individual jurisdiction can make their own policy or procedures or try to keep a database.”

Kauai Ocean Safety Supervisor Kalani Vierra said the type of snorkeling equipment worn in a drowning is something county lifeguards on the Garden Island can include in their incident reports. He added that he will bring it up at a national conference for lifeguards later this year.

Honolulu Ocean Safety Chief of Operations Kevin Allen noted that in some drownings, the mask sinks to the ocean floor during the rescue and may not be recovered. But he was also open to the idea of tracking such information when it’s available.

Dan Galanis, state epidemiologist, told the committee there were at least 149 snorkeling-related deaths in Hawaii’s waters from 2006 to 2015. Of those, 137 were visitors.

“The reality is we really don’t have the data to say snorkeling is more risky,” he said. “Right now, all we can say is a lot of our visitors die doing it.”

A Civil Beat special project, “Dying For Vacation,” published in January 2016, found Hawaii’s visitor-drowning rate is 13 times the national average and 10 times the rate of Hawaii residents. Local water safety experts have cited Hawaii’s unique ocean conditions, insufficient messaging to caution the public and the health of the individual as contributing factors.

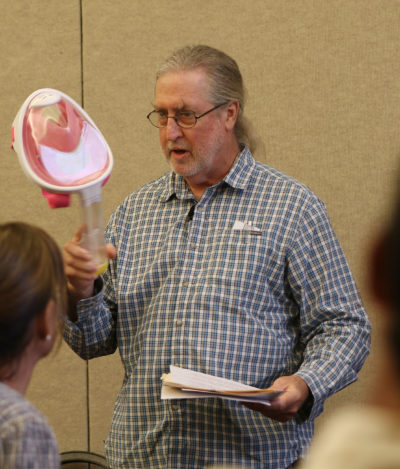

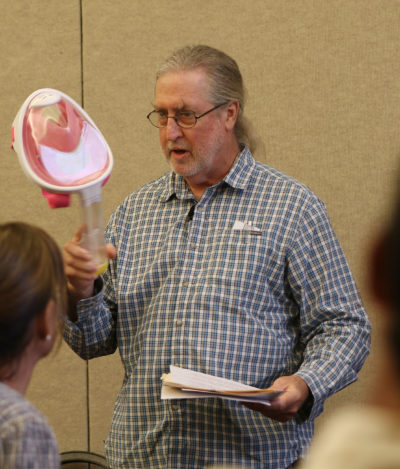

Cooper brought a full-face mask like the one his wife had to the meeting. Advisory committee members passed it around, some some of them seeing this type of mask for the first time and reacting with comments like, “I’d be claustrophobic” and “that’s weird.”

“All I ask is that you give serious consideration to the role of these new masks,” Cooper said. “Devote the resources to collect the data. Incorporate the data in incident reports and databases. Look for trends. Make the coroner aware of their use. Secure the gear as evidence. Only then will you truly be able to assess the risk.”

Mar 8, 2017

Her husband thinks a new style of mask may be to blame, but no one keeps track of the equipment being used when someone drowns.

By Nathan Eagle

Nancy Peacock walked down a boat ramp that descends into the cool blue waters of Pohoiki Bay, anxious to try her new full-face snorkeling mask in an environment where she could see parrotfish, moorish idols, corals and other sea creatures.

She had ordered the mask on Amazon and tried it out in the local pool near her California home in preparation for the September trip to visit longtime friends on the Big Island.

But less than an hour after entering the relatively calm bay, Peacock was dead.

Five months later her husband, Guy Cooper, is still searching for answers.

Did she drown because of the mask’s unique design, which covers the entire face so you can breathe out of your mouth and nose as opposed to the traditional snorkel tube in your mouth? Or was it a freak accident, even for a healthy 70-year-old who was at least somewhat familiar with Hawaii’s waters?

Cooper’s quest has brought to light significant gaps in data collection by government agencies, inadequate policies with the chain of custody for evidence and confounding decisions by the county medical examiner.

“My God, these masks could be killing others and no one has a clue,” Cooper said. “Isn’t that something you would want to know, that the public needs to know?”

He tried to warn others of what he sees as the mask’s hidden dangers by posting a review about his wife’s death on Amazon, but it has been removed from the website; he’s not sure who took it down or why.

In other reviews on Amazon and conversations with people who have used the Azorro mask, some customers have reported that it is prone to leaks and can be difficult to quickly remove because of straps designed for a snug fit. Users have also reported carbon dioxide buildups that could cause someone to pass out.

“I find this mask unusable,” Dan Deforest said in his Aug. 4 review of the mask on Amazon. “It fogs very quickly. It also does not expel all carbon dioxide before inhaling oxygen.”

“Snorkel works fine until you go under water, then it’s as though the valve at the top gets jammed and it’s like breathing through a straw,” E.G. Bradlee said in his July 27 review.

But there have also been numerous positive reviews, and hotels and tourist shops are renting out the new style of snorkeling mask with increasing frequency.

“Works as advertised,” Machael Catlin said in his Aug. 22 review. “Gives great angle of vision compared to usual masks.”

Some owners of companies carrying the mask have been promoting it in the islands as a safe piece of equipment, especially for beginners, according to lifeguards, snorkel shop owners and fire department officials. Water safety officers have been asked to endorse it, but have declined as county policies generally prohibit product endorsements.

Robert Wintner, who owns Snorkel Bob’s snorkel-rental stores on four of the Main Hawaiian Islands, said his employees tested the full-face masks.

“They have been so aggressive in their marketing. ‘You’ve got to give it a try, you’ve got to give it a try, you’ve got to give it a try,’” he said. “We tested it and said, ‘No way. We won’t carry it.’”

Wintner noted its potential for carbon dioxide buildup due to the full-face design and likelihood of leaking because of using a cheap substitute for silicon to create a secure seal when worn.

“You have to base your assessments on experience, intuition and instinct,” he said. “When I saw that thing, it didn’t look right.”

Wintner said he could see how the mask could create a situation that causes its user to panic, which ocean-safety experts often identify — along with age and underlying health conditions — as a primary reason why so many visitors die while snorkeling in Hawaii.

“I was aghast when I started looking into it,” Cooper said in January when he visited the Big Island.

He was driving south from Hilo to Pohoiki Bay, also known as Isaac Hale Beach Park, to visit the place where Peacock drowned. Cooper wanted to learn more about the incident from the lifeguards who responded from a nearby beach.

Cooper, a 68-year-old retired nurse who spent much of his career working in intensive care units, has been reaching out to government officials, water safety officers and others to piece together what happened and find ways to make snorkelers safer.

His most recent meeting was with Gerald Kosaski, the Hawaii County Fire Department’s battalion chief who oversees ocean safety.

“When something negative happens, it can bring a positive out of it,” Kosaki said. “Guy is pushing forward.”

On Sept. 6, the day Peacock drowned, Cooper was back in Martinez, California, readying for a trip they were about to take to see his family in Philadelphia. It was one of the only times they didn’t travel together.

He fondly recalled their adventures last June in Italy, where they hiked Mount Vesuvius, and their prior trips to Thailand, Japan and Cambodia — not to mention a four-month, 14,000-mile road trip across the United States in his 1968 Avion camper.

They met in 2007 at Burning Man, an annual festival of arts and music in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert. She was the first person he met there, and Cooper said they soon became inseparable.

Peacock was a costume designer as well as systems analyst and computer programmer.

“She really used both sides of the brain,” Cooper said.

It was a sunny January afternoon when he visited Pohoiki Bay, where his wife drowned, and a mix of locals and visitors were out in the water.

A handful of surfers were riding waves and a swimmer was making his way back in, passing the no-swimming sign that’s posted by the state boat ramp and routinely ignored, like so many other warning signs around Hawaii.

“Sometimes, I’m just numb,” Cooper said as he stood near the shore.

It was a surfer who first sounded the alarm. She spotted Peacock floating on her back with the mask on slightly pulled up over her mouth and nose. She grew alarmed when two small waves rolled over her and she did not respond.

The surfer paddled over and noticed Peacock was bloated and turning blue. The surfer yelled for help and kept Peacock from sinking until others came to help.

After bringing Peacock to shore, lifeguards from an adjacent beach performed CPR in shifts for half an hour as paramedics made their way to this relatively remote part of the island.

Chris Birkholme, a water safety officer for Hilo and Puna with 18 years’ experience, was one of the first on the scene. He recalled in vivid detail the effort to revive her.

“We’re here to help,” he said. “But that place is blind to us.”

There’s a lifeguard tower a few hundred feet from the bay but it’s out of sight, facing east toward the open ocean, an area with rougher waters.

Lost Mask Leads To New Policy

The snorkeling mask that Peacock was wearing went missing sometime between when she was brought to shore and when she was pronounced dead at a hospital in Hilo.

While the lifeguards and paramedics did all they could to save Peacock, Kosaki said, “there were mistakes made.”

Specifically, he said, the mask should not have been lost. Kosaki plans to make it an official policy to ensure equipment, which could become evidence to help determine a cause of death, does not get tossed out regardless of its perceived value.

He expects the policy to mandate that the equipment is first offered to the family, then the police. And if the person is transported via ambulance, the equipment goes with them.

“It’s pretty simple,” Kosaki said. “But we need it in writing.”

Cooper bought a snorkeling mask identical to the one his wife had worn and, on this visit to the Big Island, carried it with him to show lifeguards. He asked them if they had seen people wearing them lately and if they were aware of its potential hazards. Many said they had seen them and would ask people if they’ve had any problems.

Later that afternoon at Ahalanui Beach Park, a natural hot spring a mile up the road from Pohoiki, a middle-aged man was snorkeling with a similar full-face mask. He fidgeted with its fitting several times but otherwise appeared to be enjoying his experience in the placid waters.

Beef Up Database To Identify Trends?

Preserving the equipment that a person was using in a drowning is just the first step to Cooper.

He ultimately wants to see a database that logs information about the equipment in each incident so authorities can identify dangerous trends, much the same way that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration collects data to determine if a particular type of airbag is faulty in fatal car crashes.

Hawaii is not alone. Cooper has spent hours researching this issue but has been unable to find any government agency in the U.S. or abroad that has created a database that includes details about the equipment worn in a drowning or near-drowning incident.

“As I looked into it further, I was stunned to find that apparently no one in the world makes the connection,” he said. “No one is paying attention. In my wife’s case, neither the first responders nor the police nor the coroner had any concern for the equipment. My wife’s mask was just tossed in the trash. I also found no evidence of any independent testing or certification of these things.”

The Hawaii Department of Health’s Injury Prevention and Control Section compiles records about the number of ocean drownings, the location of the incident, the victim’s residence and what they were doing.

But there are few details beyond a label of “snorkeling,” for instance. Nothing about what brand of mask was worn, what type of snorkel or fins.

Cooper maintains that recording the make and manufacturer is critical. He said the Azorro brand of mask his wife wore seems to be a Chinese knock-off of the original French design.

The Azorro mask goes for $49.99 on Amazon, compared to up to $199 for the version by Tribord, which says on its website that it created the first full-face snorkeling mask “allowing you to breathe just as easily and naturally underwater as you would on land.”

Attempts to find contact information for Azorro were not successful.

A representative from Amazon.com, which sells the mask through a third party, also could not find contact information for Azorro.

But the representative, who declined to give her name, said Amazon takes product safety “very seriously,” and won’t hesitate to quit carrying a product if it’s found to be unsafe. She did not know why Cooper’s review may have been taken down but said it most likely should not have unless it violated the site’s community rules, which bans profanity.

When it comes to improving the department’s database of ocean-related incidents, Kosaki said it seems reasonable to add a new requirement to include what equipment, if any, the person was using.

“I think adding one more thing would be useful,” he said.

Kosaki plans to bring it up at the next quarterly meeting of the interagency Hawaii Drowning and Aquatic Injury Prevention Advisory Committee in March. He serves as co-chair with Jim Howe, a longtime ocean-safety expert who was recently appointed director of the Honolulu Emergency Services Department.

State epidemiologist Dan Galanis thinks the use of these full-face snorkel masks will increase over time, and that logging data about the type of gear used in a drowning incident would be useful.

“The basic design of snorkel gear really didn’t change for as long as I’ve been around to use them until these things came around,” he said. “It is definitely an unknown. I think that alone merits the distinction in their use at the autopsy level.”

But getting lifeguards or EMS personnel to log information about types of equipment would be more challenging, Galanis said.

At the autopsy level, it would just be a matter of talking to the four county medical examiners and having them add that additional level of detail in their reports.

That would help with fatalities, he said, but would not provide as robust a data set as having lifeguards log that information with each drowning or near-drowning incident. The hard part there is in the additional time involved and making it uniform across the state.

Galanis also sees an opportunity for the University of Hawaii or other research institutions to do a study of these new full-face masks to explore complaints of carbon dioxide buildup and other reported issues.

“The continuing story is people drowning while snorkeling here,” Galanis said. “It’s so persistent.”

Searching For Solutions

Hawaii had on average 58 drownings per year from 2006 to 2015, with the trend increasing since 2010, according to the most recent Department of Health data.

And visitors continue to die in Hawaii’s waters at a higher rate than residents, with snorkeling being the most common activity.

“We have identified that snorkeling is the reason why many visitors drown but we’ve never looked at the equipment,” Kosaki said.

A Civil Beat special project, published in January 2016, found Hawaii’s visitor-drowning rate is 13 times the national average and 10 times the rate of Hawaii residents. Local water safety experts have cited Hawaii’s unique ocean conditions, insufficient messaging to caution the public and the health of the individual as contributing factors.

Despite this longstanding problem, the state lacks specific prevention strategies, Galanis said, but it’s working toward them.

The Hawaii Drowning and Aquatic Injury Prevention Advisory Committee — which includes health officials, the Hawaii Tourism Authority, emergency responders, ocean safety advocates and others — has been working the past year to develop a safety message that could be disseminated to warn visitors of Hawaii’s hazardous waters.

At Black Rock, for instance, a popular tourist destination on the southwest shore of Maui, at least 21 people have drowned over the past decade. All but one was a visitor and two-thirds were snorkeling.

Looking at the demographics, 86 percent were male, 76 percent were over 40 years old and 43 percent had an underlying heart disease, according to the Department of Health, which compiled data from paramedics.

Delving Deeper Into Causes Of Drowning

Cooper has concerns about blaming a drowning solely on someone’s age and overall health. He said it’s worth looking deeper: Did something trigger a heart attack in the water, for instance, such as a mask that suddenly flooded with water?

He found discrepancies in his wife’s autopsy report from the Hilo Medical Center.

The autopsy notes a “reported history of heart condition,” he said, but he is perplexed at to where that information came from because no one asked him about her health history.

The autopsy also lists “ischemic cardiac disease” as a contributing factor in her death even though she had no history of it, he said. Peacock had a history of moderate hypertension that was controlled with medicine, he said, adding that the physical findings in the autopsy and the estimations of her own cardiologist did not support the ischemic cardiac disease determination.

Cooper flew to the Big Island the day after he learned that Peacock had drowned. It was his first time in Hawaii since 1970, when he was stationed at Hickam Air Force Base on Oahu.

“My point in reviewing all of this is that I think something else led to Nancy’s death that has implications generally for ocean safety, particularly as regards snorkeling,” Cooper wrote in a Dec. 7 letter to the doctors who pronounced her dead and performed the autopsy.

“I would think that any coroner investigation would insist this evidence be secured and examined,” he wrote. “This feedback seems critical to me. As doctors responsible for response and evaluation of such emergencies, I would hope that you would consider and spread the word that such information is crucial. You need it. First responders need it. Lifeguards need it. Consumers need it. And the snorkeling industry needs it.”

Cooper said he did not hear back from the doctors.

“I’m back in Hawaii not only to be close to where she last was, but to escape the life we shared,” Cooper said in an email last week.

He plans to attend the Hawaii Drowning and Aquatic Injury Prevention Advisory Committee’s March 15 meeting. The agenda includes a review of “lifeguard log and incident reporting in application to (drowning prevention).”

“That’s what I want to do — just get the word out — and hopefully prevent some of these,” Cooper said.

Bridget Velasco, state drowning and spinal cord injury prevention coordinator and a member of the advisory committee, said there are remarkably few proven strategies for drowning prevention, and even less for prevention of drowning during snorkeling.

“We look forward to disseminating clear and accurate information but the process to get to that point is tedious and time-taking,” she said.

Cooper said he’ll probably never know the cause of Peacock’s death.

“Did she run out of air? Did a faulty mask flood with water? Did she quietly succumb to a buildup of CO2? Did she really have a heart attack?” he wrote in the email. “I suspect equipment failure and strongly suggest that it be considered in every case such as this. At the least, in the interest of public safety, some effort should be made to to secure, examine and record such information, so that potential equipment problems and/or trends might come to light. It could save lives.”

Jan 1, 2016

Yet state, county and even tourism officials are doing little to try to reduce what’s become one of the highest rates of visitor deaths in the nation

By Nathan Eable, Marina Riker

Married 32 years, Jane and Bob Jones did a lot in life together. They raised a family, served those in need and traveled when they could.

They died together, too.

The Joneses drowned in Hawaii, on a vacation aimed at escaping wintry Washington state weather for sun and sand.

On a Friday last March, the couple decided to snorkel the azure waters of Hanauma Bay, a popular tourist destination a half-hour east of Honolulu. They were a few hundred yards from the beach in an area called Witches Brew. Witnesses said one of them got in trouble and the other tried to help. Lifeguards responded but it was too late.

A longtime social worker, Jane, 55, coordinated free medical clinics and advocated for the homeless. Bob, 60, a retired Army captain, was a volunteer firefighter and worked for the Troops to Teachers program that helps military personnel start new careers.

“They were real ‘sparkplugs’ for the community, always looking for ways to serve the marginalized among us and working for justice,” David Ammons, a fellow parishioner at Westminster Presbyterian, told The Olympian newspaper. “Together, they made a real difference.”

The Joneses were not unlike others who have come to Hawaii for vacation, lured by the majesty and mystique conveyed by countless visitor publications, movies and magazines, songs and social media.

But like dozens of other visitors, the Joneses died in a manner that’s becoming all too familiar in the islands.

Drowning is by far the leading cause of death for tourists in Hawaii and snorkeling is the most common activity that leads to visitor drownings.

State health department records over the past decade show that Hawaii’s visitor-drowning rate is 13 times the national average and 10 times the rate of Hawaii residents.

Since July 2012, at least 147 visitors — nearly one a week on average — have died in Hawaii from injuries suffered while doing common tourist activities like swimming, snorkeling, hiking and going on scenic drives.

Many also have sustained serious injuries, especially spinal cord damage.

The state, counties and tourism industry spend millions of dollars on lifeguards, warning signs, informational websites, safety videos and other strategies to keep people safe.

But a Civil Beat review of tourist deaths over the last three and a half years suggests safety is far from the top concern when it comes to the 8 million visitors who travel to the islands every year.

Hawaii lacks clear and consistent safety messages to target visitors before they arrive. Even the Hawaii Tourism Authority’s main safety website contains broken links to online resources.

Although many visitors now use social media sites like Facebook, Twitter and other online sites to plan vacations and find activities, government officials and tourism industry leaders have done little to develop a social media presence that promotes safety.

Experts say the key to injury prevention is getting that message in front of visitors as many times as possible — whether it’s through websites like Yelp! or in-flight videos and brochures in hotel rooms.

Former lifeguards, emergency room physicians and other safety experts have for years lobbied state legislators and policymakers to prevent injuries and deaths by getting timely and useful information — current ocean conditions, the latest trail closures, general safety tips — disseminated as widely as possible.

But local and state officials have paid little attention to efforts to strengthen safety programs or test whether those that are in place are effective.

For instance, tourism officials have started playing videos at airports and car rental companies, putting more brochures in hotel rooms, passing out pamphlets and adding more warning signs. But it’s unclear whether tourists are paying attention.

Dr. Monty Downs, an emergency room physician and longtime ocean-safety advocate on Kauai, estimates that only a small number of people see the videos at baggage carousels — although there is evidence that at least one man’s life was saved as a result of information his son obtained from the airport video.

Downs has been focused instead on expanding statewide a rescue tube program that’s seen success on Kauai. The tubes have been in place at unguarded beaches around the Garden Isle for more than six years, and rescues using them are regularly reported.

The Hawaii Tourism Authority recently created a new in-flight safety video under a 2013 legislative mandate, but it’s not shown on any flights yet from the mainland or overseas and some consider it too soft on safety.

Many in the industry now question whether the video was a waste of time and money given the historic lack of cooperation from airlines — and logistical challenges — to show safety messages. Plus, many passengers are simply not paying attention to the in-flight videos and entertainment because they are focused on their smart phone, tablet, book or magazine.

Commercial tour companies tout their own safety programs in an effort to convince tourists to snorkel, surf, kayak or rent various thrill craft with them. In general, experts say many of these companies give visitors a safe way to participate in an activity — often safer than on their own when there’s direct supervision.

But there’s no good way of knowing what companies are operating aboveboard and which ones are just trying to make a quick buck. The state only started requiring all operators to obtain a commercial permit in late 2014. And to avoid liability, the program leaves it up to the businesses to hire qualified, competent staff.

Meanwhile, nonprofits have been created whose focus is to help visitors cope with tragedies experienced while on vacation in Hawaii, whether it’s how to send a body to the mainland or arranging counseling to deal with an untimely death.

These are the kinds of things that guidebooks don’t provide, online sites underplay and the tourism industry shies away from.

Yet, the Aloha State’s drowning rate for visitors is so much higher than the national average. Hawaii’s visitor drowning rate — 5.7 per 1 million visitor arrivals — dwarfs those in states like North Carolina and Florida, where drowning rates are .5 and .9 drownings per 1 million visitors, respectively.

Drowning has been the leading cause of fatal injuries for visitors for decades. From 2005 to 2014, 49 percent of visitors who died of injuries did so by drowning, compared to just 5 percent for locals, according to state Department of Health data.

It’s particularly significant on Kauai and Maui, where visitors comprise almost three-fourths of all fatal injuries. Experts say that is partly due to the stronger visitor presence on the neighbor islands compared to Oahu. On Maui, for instance, roughly one in four people on any given day is a tourist.

Clearly, experts say, Hawaii residents know something about staying safe in the ocean that tourists don’t, and that vital information is not reaching those who need it.

“There’s a Hawaii vacation mentality that, ‘I can do anything I want here because I’m in paradise,’” said Jessica Rich, president of the Visitor Aloha Society of Hawaii. “They take risks here that they would never take at home.”

Some visitors increase their chance of a fatal accident by combining alcohol with a dip in unfamiliar waters or simply exercising poor judgment.

But many fail to understand the risk they are taking in the first place — inadequate trip preparation, bad decisions by tour guides or a lack of sufficient warning of inherent dangers.

In the last few years, the number of visitor deaths has increased, mirroring the state’s successful push to increase tourism especially from areas on the mainland and abroad that don’t have beaches or the kind of scenic ocean attractions found in Hawaii.

Visitor arrivals hit a new record in November with 661,352 people arriving in that month alone. Just over 43 percent came from the western United States, according to the Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism. Japanese arrivals numbered 122,840 and there were 119,167 visitors from the eastern U.S.

With 2016 expected to be another record year for tourism, a new task force is exploring ways to improve ocean safety. In September, a committee of 12 key players from Hawaii’s various tourist and ocean safety agencies met for the first time.

“We’ve done a really, really good job of branding Hawaii. We’ve done a really good job of marketing and getting people here,” said Jim Howe, a longtime ocean safety advocate who chairs the new Drowning and Aquatic Injury Prevention Advisory Committee.

“What I think is missing is that we oftentimes don’t tell people about some of the issues that they may face when they get here, and how to either avoid those, No. 1, or if they find themselves in those circumstances, what to do.”

So far, the committee has been working to come up with options to help raise public awareness, both before tourists arrive and once they get here. Some of those ideas include more meaningful and engaging in-flight videos and partnering with online review sites. The committee also is looking at identifying beaches that might need more lifeguards or better warning signs.

“Social media and the Internet are the key players in this game right now,” said Howe, who recently retired from his job as Honolulu’s chief of ocean safety operations. “They’re not going on guided tours, but they need that information.”

As more visitors opt for alternative accommodations through Airbnb and vacation rentals, they’re even less likely to book tourist activities through hotels that might recommend tour guides who offer safe excursions.

Instead, those visitors are planning their itineraries through sites like Yelp! or TripAdvisor. But those websites don’t provide the same safety advice that a tour guide might when visiting dangerous locations like Halona Blowhole or Spitting Caves on Oahu.

“Many visitors are basically like our toddlers in terms of their understanding of what’s going on at the beach and in the ocean,” Howe said. “This may be a 37-year-old adult, but if you look at their beach IQ, they’re about a 2-year-old.”

That’s part of why every week on average, somewhere in Hawaii, a tourist dies while involved in what should be common — and safe — activities.

Most tourists who die get at least a short write-up in the local paper or a news website.

It was the frequency of those stories that caught our attention a few years ago. It’s not the kind of story you see with such alarming regularity anywhere else in the country, even in big tourist markets like California or Florida, or rugged adventure travel areas like Alaska.

The stories, along with autopsy reports and other official records, formed the basis for a database that allowed us to analyze visitor deaths in a comprehensive and compelling manner. Our staff visited some of the sites that, the data shows, pose the greatest risk for out-of-state visitors. They interviewed numerous ocean safety experts, state and local officials who track visitor deaths, and people who work for the nonprofit organizations that help when tragedy strikes. They tracked down family members who lost loved ones here in the islands.

We created a database of 147 tourist deaths over the past four years, compiled from media reports we’ve been saving since July 2012 along with autopsies from the Honolulu medical examiner. Neighbor island medical examiners said they couldn’t provide similar reports.

We also relied on a Hawaii Department of Health report for this series, showing non-resident deaths over the past decade.

The data, including the state’s records, are consistent: When visitors die from injuries, the vast majority die by drowning. And of the ocean activities they were doing at the time, snorkeling was No. 1.

In the past four years, people were swept out to sea while climbing on rocks near the shoreline, some perished in car or moped accidents, and several died while hiking.

A significant number of tourists who died were males in their 50s or 60s, some, as it turned out, with underlying heart conditions.

“We’d really like to say, ‘Hey, exercise a few months before,’” said Jeff Murray, chief of the Maui County Fire Department. “People should understand their limits, number one, and ask questions.”

Hawaii’s unique ocean conditions can look deceptively mild to visitors. Experts say the physical characteristics found only in the Hawaiian Islands — the way the surf pounds and currents rip — often surprise visitors who were expecting the glassy waters seen on many postcards.

The state and counties put up signs warning of unsafe conditions — for instance, high surf or strong shore breaks — but mostly just at public beach parks. These signs are often ignored, and ocean safety experts say they don’t go far enough to deter visitors from going into the water on dangerous days.

Todd Duitsman was paralyzed from the neck down while on a family vacation to Maui in July 2014. He said he saw the signs warning of the shore break — before diving head-first into the sand.

“There’s a certain personality where it doesn’t matter how many signs you put up, I’m still going to frolic in the ocean,” he told Civil Beat.

Guided tours also don’t guarantee safety.

Tyler Madoff, a 15-year-old star athlete and honor student from New York, drowned during a kayaking trip on the Big Island in July 2012.

He was on a guided tour with a dozen other teens from across the country. At lunch, the guides led them down a trail to see tide pools and “the real Hawaii.” A rogue wave rushed over the rocky coastline and pulled Tyler out to sea. His body was never recovered.

Other visitors get into trouble on their own.

Cheryl Black, 55, was a financial manager at an auto dealership in Texas. She was hiking at Oheo Gulch on Maui in June 2014 when she fell 15 feet off a ledge. Firefighters found bystanders giving the woman CPR while she lay unconscious, halfway in the water.

The gulch, also called Seven Sacred Falls, is promoted as a must-see spot on a trip to the Valley Isle.

Cheryl left behind a husband and two sons. Friends and family penned heartfelt memorials, calling her a “warm and wonderful woman” who was “loved by all that knew her.”

Dan Galanis, the state epidemiologist who has spent the past two decades analyzing injury data and prevention techniques, said the advisory committee’s formation marks the first time people from around the state have been convened on this issue in a sustained manner.

“I don’t think it’s going to magically solve the problem overnight, but it’s definitely the first needed steps for bringing a coordinated approach to this problem statewide,” he said.

Safety advocates say the balance between promoting Hawaii to visitors and protecting them has tilted too far in favor of the tourism industry over the past few decades, but there’s optimism that it can be leveled.

“There really is a sea change of attitude and kind of perspective that we feel is really timely right now,” said Bridget Velasco, the state drowning and spinal cord injury prevention coordinator.

Her position was created in the past year, and she’s responsible for pulling together the advisory committee over the past six months. Velasco said solid evidence — and the data — will steer the committee.

“Hawaii Tourism Authority has said we realize we are bringing people here and we need to keep them safe, and that’s part of their mission now,” she said. “Being able to partner with them is huge.”

Jadie Goo’s main responsibilities for the Hawaii Tourism Authority are safety programs, the China and Taiwan markets, and workforce development. She said keeping visitors safe is a collaborative and collective effort.

Just from a budget point of view, HTA is mandated to allocate a certain percentage to safety programs. For fiscal 2016, the agency budgeted $680,000, which is $270,000 more than required.

“The key word is balance,” Goo said. “We want to develop consistent, strong messages to inform visitors. But we don’t want to scare them away.”

Jan 1, 2016

Breathing through a tube is uniquely challenging. And it can turn deadly for those who have health issues but don’t recognize the risk.

BY MARINA RIKER,NATHAN EAGLE

Lifeguards pulled Alexa DiGiorgio from Hanauma Bay just before 10am on a Sunday in June 2014. The New Jersey resident had been snorkeling 50 yards offshore while her husband, Marc, helped his children and sister, who had never snorkeled before.

“When we got back to the beach, I realized I couldn’t see Alexa so I went back into the water to look for her,” Marc DiGiorgio told The Westfield Leader and The Scotch Plains-Fanwood Times. “Then I heard the sirens.”

Lifeguards found Alexa in less than 3 feet of water. They pulled her to shore, where she received first aid.

DiGiorgio was taken in critical condition to an Oahu hospital, where she died. She was 42.

Despite being touted as a leisure activity, snorkeling is the most common cause of injury-related death in the islands. In the last 10 years, more than half of all visitors who drowned in the Aloha State did so while snorkeling.

Hanauma Bay, an iconic nature preserve, receives more than 1 million visitors annually. More tourists drown there than anywhere else in the state. But it is far from the only location where Hawaii’s visitors run into trouble while snorkeling.

“A lot of people think, ‘Well, Hanauma Bay is really shallow, so if I get into trouble, I’ll just stand up.’ Well, a lot of the rescues and drownings occur in waist-deep water,” said Alan Hong, an avid waterman who managed the bay for 21 years.

“For a neophyte snorkeler, what you don’t realize is when you’re wearing fins, it’s not an easy thing to stand up in very shallow water because this extended foot length that the fin causes makes it very difficult to get your feet under you when you’re floating face down,” he said.

“So if you get a gulp of water in you, and you start to gag and you decide to try to stand up, it could be several more seconds before you get your feet under you in a way that you can stand up, and by then you’ve taken another gulp and it’s downhill from there.”

Officials with the Honolulu Parks Department and Hanauma Bay’s current manager did not respond to requests for an interview for this story.

State Department of Health data shows that since 2005, more than 128 visitors have drowned snorkeling in Hawaii’s waters, from Kaanapali on Maui to Shark’s Cove on Oahu to Haena Beach Park on Kauai.

Of those, most were men in their 50s and 60s, and more than 40 percent had heart conditions.

Most of the deaths occurred in less than 3 feet of water.

Jung Aee Kim was an active member of the Korean community in Dallas. She sang in the St. Andrew Kim Catholic Church choir and volunteered in the community. She was also a champion amateur golfer.

In August, the 75-year-old took a vacation to Maui with her family. Her last day was spent snorkeling in “Turtle Town” with a tour group outside of Maalaea Harbor.

The Texas resident was found face down in the water around the vessel and was brought back on board. A bystander began CPR as the vessel traveled about 30 minutes back to Maalaea Harbor to meet with paramedics, but she was pronounced dead shortly after the tour group arrived.

Health professionals say the key to survival is being able to get the victim out of the water — and to medical attention — as quickly as possible.

Nearly 80 percent more drownings happened two miles away from a lifeguard tower than within a half-mile, according to Hawaii Department of Health data.

Yet due to the relatively stationary nature of snorkeling, it can be difficult for tour operators, lifeguards or others to spot a person in distress.

“When you’ve got six or seven hundred people face down, and you’re trying to figure out which one didn’t move in the last 30 seconds, that’s pretty hard to figure out,” said Jim Howe, who recently retired as chief of Honolulu’s Ocean Safety division.

Mark Vu, an anesthesiologist at Queen’s Medical Center in Honolulu, said breathing through a snorkel poses a unique challenge for swimmers. The situation can turn deadly when combined with a pre-existing health condition.

“Visitors who come to Hawaii may not be good swimmers … and likely overexert themselves doing an activity they are not familiar with like swimming or snorkeling,” he said. “They quickly become physically overwhelmed.”

The physics of using a snorkel also can add to the risk. Snorkels have a “dead space” of bad air — the air that is being exhaled but stays in the snorkel tube. Snorkelers have to get fresh air by breathing through the dead space. But that can increase carbon dioxide in a person’s blood.

“The rise in carbon dioxide in your body makes you sleepy,” Vu said. “Sleepy snorkelers eventually drown.”

Medical experts say other aspects of a vacation in Hawaii — like prolonged sun exposure or one too many mai tais — can further increase visitors’ risk of drowning by adding to their exhaustion.

Roughly 14 percent of drowning victims in Hawaii have traces of alcohol in their system, according to Health Department data.

Dan Galanis, a state epidemiologist, said interpreting the data can be challenging.

“Is there something inherently risky about snorkeling, or is it just something that’s just pretty widely available when you come here as a visitor and it’s something you’re going to do besides just swimming? It’s probably a little bit of both,” he said.

“We do think that the act of snorkeling imposes physical challenges for some people that might contribute to the drowning chain of events,” Galanis said. “We want to promote awareness that snorkeling does require a level of fitness; there is a bit of a learning curve.”

Ocean safety personnel say unfamiliarity with snorkeling and ocean conditions is the top reason visitors get themselves in trouble while snorkeling.

“They’re probably the least qualified in assessing their abilities in the ocean, and also their abilities to assess what the ocean conditions are and what abilities will be required to safely partake in the ocean,” said Hong.

A simple online search shows many marine tour companies sell snorkeling as an activity that anyone can do. And for some companies, it’s “no problem” if a visitor doesn’t know how to swim.

Most snorkel tour and rental companies provide training on how to use a snorkel. But only prior snorkeling experience can prepare visitors for water in their mask or navigating the currents, reefs and waves in Hawaii.

Snorkel Bob’s, the largest snorkeling outfit in the state, teaches visitors how to adjust a snorkel and mask. The company also gives out a safety pamphlet to each customer.

Robert Wintner, the owner of Snorkel Bob’s, said having durable and well-fitting snorkeling equipment is paramount to preventing accidents in the water.

“If your mask leaks, it will really exacerbate the feeling of panic,” he said. “If you’re short on breath and you add a couple of teaspoons of salt water in the mask, it’s a bad situation.”

Wintner said most people get in trouble because they panic, which can easily happen when they breath in water from their snorkel. He said it’s also common that his customers have never snorkeled before.

“I’ve been amazed personally that a number of people that snorkel here have never seen the ocean,” Wintner said.

Josh Guerra, a lifeguard at Hanauma Bay and a personal watercraft rescuer for Honolulu’s Ocean Safety and Lifeguard Services Division, said all of this leads to problems at the state’s busiest snorkeling destination — Hanauma Bay.

“I’ve heard people tell me that the tour operators are telling them, ‘Oh, you don’t have to know how to swim or snorkel,’” he said. “You actually need to be a pretty strong swimmer and very comfortable in the water to use a mask and snorkel because your breathing is limited.”

Guerra rescues two to six visitors a day, often in 2 to 3 feet of water.

Problems arise when people try to avoid standing on the sharp coral of the underwater reefs they are viewing.

Coral that’s already threatened by bleaching and other environmental factors can be damaged when touched by snorkelers or their fins. So many tour operators tell visitors to avoid stepping on it.

But that can be a problem if they are struggling.

“We’ve got the folks who run the preserves saying don’t stand on the reef because it’s going to hurt the reef environmentally, but we’ve got the lifeguards saying if you’re in trouble, stand up so you don’t die,” Howe said. “It’s very difficult for the visitor to understand. Who do I listen to? Well, in my world, stand up, don’t die.”